Edward Jenner had it easy. Swab some cowpox in 1796, scratch the nastiness into the arm of a little kid (see below), and, PRESTO, instant immortality.

Vaccine success after vaccine success followed. Measles, mumps, rubella, polio... one after another global scourge quaked before the mighty pipettes of vaccine researchers.

I admit, the stalwarts who discovered those vaccines did more than transfer cow-pus to an un-consented minor research subject prior to doing a victory lap around the farm. Rather, they earned their laurels by working hard, and by being brilliant.

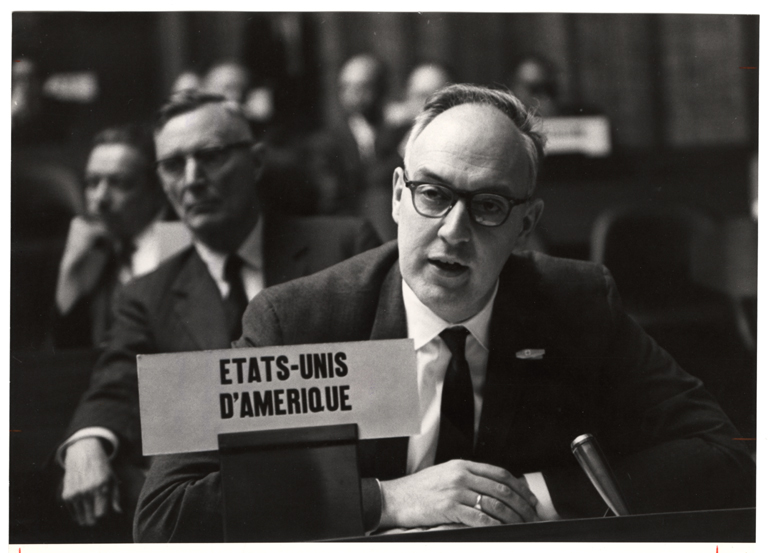

But ease wrought hubris, and as deadly viral menaces fell in succession, you could forgive one noted twentieth century sage, US Surgeon General William Stewart (pictured below), for saying, "It’s time to close the books on infectious diseases, declare the war against pestilence won, and shift national resources to such chronic problems as cancer and heart disease."

Whoops!

These early triumphs gave way to a long, hard slog. Vaccines against HIV, tuberculosis, herpes, staphylococci, and hepatitis C, among others, have proven far more elusive. Amid small successes, and spectacular failures, we have discovered an uncomfortable fact: we don't really know what makes a good vaccine tick.

This week I was glad to contribute both heat and noise to the mix. In an op-ed in the Health Affairs blog, I write about the dangers of dogmatism and the lessons learned on the road to a new HIV vaccine. And, we also published preclinical data this week on a new scalable version of our tuberculosis vaccine. Data from our Phase 1 trial of the same vaccine should come out soon!

Who knows if all this will lead to glory. Probably not! Either way, it's been a pleasure to try.

![[ M U R M U R S ]](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/51efa33ce4b09afa04cb2a66/1376911411704-LDY4UEIH1WRGPUXTMLJU/Logo.jpg?format=1500w)